A Brief Overview of MI Concepts

The Spirit of MI

While it is essential that practitioners become skilled at the behavioral skills of MI, if practitioners don’t use the skills within an ‘MI spirit’ framework they probably won’t be conducting a motivational interview. The spirit of MI is achieved by maintaining a worldview about how your interactions with clients should be like. The spirit of MI is expressed through the acronym PACE: Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). The practitioner tries to maintain an egalitarian relationship through reducing their expert role. Practitioners avoid confrontation and avoid giving advice without permission in order to establish an equal partnership. The goal is to help the client to feel accepted despite their problems through empathic listening. The practitioner instead focuses on the goals of the client rather than what is easiest or convenient for the practitioner. Instead of telling client how and why clients ought to change, practitioners explicitly attempt to evoke from their clients what their clients think about their own goals and about change.

Definitions of MI

There are three current definitions described in the latest MI book written by Miller & Rollnick (2013). Each definition captures different aspects of what MI is.

1. Motivational interviewing is a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change.

2. Motivational interviewing is a person-centered counseling style for addressing the common problem of ambivalence about change.

3. Motivational interviewing is a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change. It is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion.

The Micro Skills

The “micro skills” of MI are four general counseling skills that are used purposively throughout the MI processes. These skills are described through the acronym OARS: Open ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summary statements.

Open ended questions are used to elicit information and are often used to help clients talk about change in a more productive manner. One of the primary purposes of MI is to help clients talk themselves into changing their behavior in a positive way. Therefore, the strategic use of open ended questions is used to help clients to talk in ways that facilitate clients hearing their own thoughts about changing. The idea is that the more they hear themselves speak about why they want to or ought to change, more likely it will be that they will. It is essential then that more open ended questions are used than closed ended questions (which are often answered with a short answer or a yes/no).

Affirmations are statements that help solidify clients’ strengths, values, good intentions, coping skills, and successes. Affirmations are positive statements about these aspects of the client in ways that build their confidence. These positive affirmations should be used periodically as needed throughout the MI processes.

Reflections are statements (not questions) made by the practitioners that mirror back to the client aspects of what the client has just articulated. Using reflections does not mean that the practitioner parrots back to their clients what they have said. Instead, effective reflective listening uses different words to paraphrase or describe what the client has said. Complex reflective listening moves beyond mirroring content that the client has stated but also inferring content the client has not yet articulated. There are many different types of reflective statements which can be used purposively for different effects throughout the MI processes. For instance, reflections can help clients feel listened to and empathized with, talk more about change, express unspoken emotions or thoughts, begin to plan their change process, or help the practitioner steer the conversation in non-confrontational ways.

Summary statements are considered long-reflections where the practitioner mirrors back to the client different elements of their conversation which have occurred over time, not just what is currently being stated. Practitioners using summary statements will gather together several aspects of what their client has been stating over a period of time and lump them together in a statement. Summary statements can be used to transition topics, reinforce specific content, and link or collect different elements of the conversation together.

The Principles and Processes of MI

The micro skills are used to support the guiding MI principles, which include: (a) expressing empathy, (b) developing discrepancy, (c) rolling with resistance (or dance with discord), and (d) supporting self-efficacy. These principles are described further in the description of the four processes.

The Four Processes

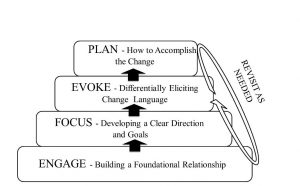

There are four counseling processes articulated in MI: Engagement, focusing, evoking, and planning (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). These four processes can be viewed as building on one another, each process being foundational and requisite in order to proceed to the next (see Figure 1). While on the surface the four processes of MI might seem linear, they are not, and practitioners will revisit prior processes based on client language and circumstance as needed (Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

Figure 1: The four processes of motivational interviewing

Engaging: The purpose engagement process is to build trust and a working relationship with the client. People are often unwilling to be honest and disclose more fully to a practitioner if they don’t feel the practitioner is trustworthy. Therefore, the goal of the practitioner during the engagement process is to build a working alliance. One of the primary ways to develop trust is to express empathy for the client and their situation. Expressing empathy is one of the primary principles of MI, and skillful reflective listening is one of the primary strategies for helping someone feel empathized with. Another primary principle of MI often used during engagement is Rolling with Resistance (or Dancing with Discord). The concept of rolling with resistance is to avoid confrontation or defensiveness when resistance or discord is present but instead help the client explore the discord. The goal is to instead help the client articulate his or her underlying concerns.

Focusing: The purpose of the focusing process is to help the client and practitioner agree on the topic or topics which will be covered during the session. The focusing process is about finding an overarching direction and—within that direction—more specific achievable goals and objectives (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). During the focusing process the practitioner purposively uses the micro OARS skills of MI to help a client choose a topic and then stay on topic once chosen. Periodically it may be important to re-map the agenda for the session if necessary through refocusing.

Evoking: Once a client and practitioner have collaboratively picked a target behavior, the practitioner will move into the evocation process. The purpose of the evocation process is to structure the conversation so that the client talks themselves into changing. One of the MI principles often used in the evocation process is developing discrepancy. This occurs when practitioners facilitate a conversation where they help clients to identify the discrepancy between their current behavior and their ultimate goals and values. This is accomplished from the client’s internal perspective, not from the practitioner’s external perspective. The goal is to help the client to experience a greater sense of internal discrepancy between their current behavior and their desired future. This increased discrepancy is then reduced as clients decide to take steps to accomplish their goal. The greater the discrepancy between a behavior and a goal the more importance a client may place on achieving that goal. One of the primary means for developing discrepancy is eliciting change talk. Eliciting change talk is accomplished through differentially and strategically eliciting the desires, abilities, reasons, and needs for change (Change Talk) that a client is thinking about in relation to a specific target behavior. This does not mean that the desires, inabilities to change, reasons and needs to stay the same (Sustain Talk) are ignored. Instead, the goal is to help the client to feel heard and empathized with when sustain talk occurs. At the same time, the practitioner will start to rescue change talk from the ambivalence that a client is expressing. If a client never transitions to offering more change talk than sustain talk, the likelihood that they will be able to increase their commitment to change is reduced. Therefore, the practitioner will purposively use the micro OARS skills to help the client talk more about their desires and abilities to change than why they are stuck. Throughout the evocation process, preference is given to the client’s ideas about why they want to change. The practitioner avoids telling the client why or how the practitioner thinks he or she should or ought to change. Another principle often used throughout MI, but particularly in evocation is supporting self-efficacy. Practitioners will look for opportunities to build clients belief in their capacity to make a change. As clients’ confidence in their ability to make a change increases the likelihood that they will be willing to take steps toward a goal increases. Practitioners can help clients increase their confidence by helping clients talk about current or past successes, strengths, coping skills, good intentions, pro-social actions, and core values. As the practitioner helps clients to articulate these things, the practitioner will strategically affirm the client in order to increase their confidence.

Planning: The purpose of the planning process is to help the client mobilize their change talk into making a commitment for change. This commitment is often followed by the development of small, achievable goals that will help them move toward behavior change. As in evocation, preference is given to how the client envisions themselves changing rather than how the practitioner thinks the client ought to go about changing. Frequently practitioners will jump to the planning process too early. If this happens, often clients will push back or become more ambivalent. If the client becomes resistant or discord become present in the relationship the practitioner might consider moving back to the engagement process. If the client becomes more ambivalent but still appears to have a good working relationship with the practitioner, the practitioner might consider moving back to the evocation process. The planning process is about helping the client articulate their own plan for change. If the client gets stuck during the process but is still highly motivated and committed, the practitioner might consider asking permission to provide some help, preferably through a menu of options.

Types of Language

There are four different types of language that it is essential to pay attention to when conducting motivational interviewing. These different types of language can give the practitioners clues about which process might be most important to use in a given moment. As indicated previously, the four processes of MI are not always linear. Sometimes the practitioner will be required to move back and forth between them as needed. The four types of language the practitioner should be attuned to listening for are: discord, sustain, change, and commitment talk.

Discord: Discord (or resistance) occurs when a client indicates through non-verbal or verbal communication that they do not trust the practitioner or the system the practitioner represents. Discord essentially means that the client and the practitioner are not on the same page and that their working alliance is in danger. Having a positive relationship with the client is fundamental to being able to conduct motivational interviewing. Discord is often expressed through statements about the relationship with the practitioner and is often emotionally based. For instance: “I’ve heard about vocational rehabilitation. You don’t really care about what I want to do for work, you just want a quick number” or “You don’t have a disability so you couldn’t possibly understand me”. If discord becomes apparent during an interview a practitioner using MI should repair the relationship by dropping back to the engagement process instead of moving forward.

Sustain Talk and Change Talk: These two types of language occur when ambivalence is present regarding a specific target behavior. The client’s expressed desires to stay the same, inabilities to change, reasons to stay the same, and needs to stay the same are called sustain talk. The client’s desires, abilities, reasons, and needs to change are called change talk. Sustain talk occurs when a client talks about barriers to change such as “It’s too hard,” “I’ll lose my social security benefits if I go back to work”, or “I don’t know if I can handle it.” Change talk occurs when a client talks about why they are interested in or are even thinking about changing, for instance, “I want to be able to make more money”, “being able to live on my own would be awesome!”, or “I’d love to get my probation officer off of my back.” During the evocation process the practitioner will attempt to help the client articulate as much change talk as they can. This helps the client to resolve their ambivalence about change and if done well increases the client’s importance and confidence for making a change. However, there are also times when a practitioner might consider maintaining balance between the change and sustain talk that they hear, and they won’t try to elicit one side of the client’s ambivalence over the other. The maintaining of balance when interviewing is called counseling with neutrality or equipoise (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Miller, 2012). Equipoise is maintained when helping someone decide between two equally beneficial or neutral options (e.g. choosing between two jobs each of which has its pros and cons). Ambivalence can still be resolved when maintaining equipoise through the exploration of goals and values; however, the practitioner is more careful about not eliciting greater sustain or change talk. However, in most instances the client and practitioner will have collaboratively determined what the target behavior is and have a shared understanding and direction about where they would like to go. When the target behavior is clear and there is not an ethical dilemma about maintaining neutrality in the evocation process, the practitioner will purposively use the micro OARS skills to elicit more change talk than sustain talk. As the practitioner is successful at structuring the conversation in this way the client’s internal motivation will increase and the likelihood that clients will resolve their ambivalence goes up. As a client begins to resolve their ambivalence the practitioner will mobilize the change talk they have heard into helping the client make a commitment for change. This often occurs through summarizing the change talk that the practitioner has heard the client state and then asking a key question to help the client transition into planning, such as: “So given all that we have been talking about, what do you think you’ll do?” or “Where should we go from here?”

Commitment Talk: Commitment is often present when a person has resolved their ambivalence. This is often represented by statements such as “I’m going to do this” or “Yep, I’ve decided” etc. These types of statements often indicate resolve and intention to make a change. Sometimes commitment is illustrated through a willingness to make small steps such as, “I’m going to start submitting applications tomorrow!” Practitioners will capitalize on this commitment by helping the client articulate and develop a realistic plan for changing.